Read The Full Article On: Latimes

The Los Angeles Times is committed to reviewing new theatrical film releases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because moviegoing carries inherent risks during this time, we remind readers to follow health and safety guidelines as outlined by the CDC and local health officials. We will continue to note the various ways readers can see each new film, including drive-in theaters in the Southland and VOD/streaming options when available.

The past few years have brought a fresh resurgence of interest in the life and legacy of Nikola Tesla, the popularity of an Elon Musk electric car being only the best-known example. You can find Tesla’s tall, dark-suited frame and mustachioed frown in graphic novels and video games; you can hear his innovations extolled in the lyrics of rock songs and even a 2018 stage musical.

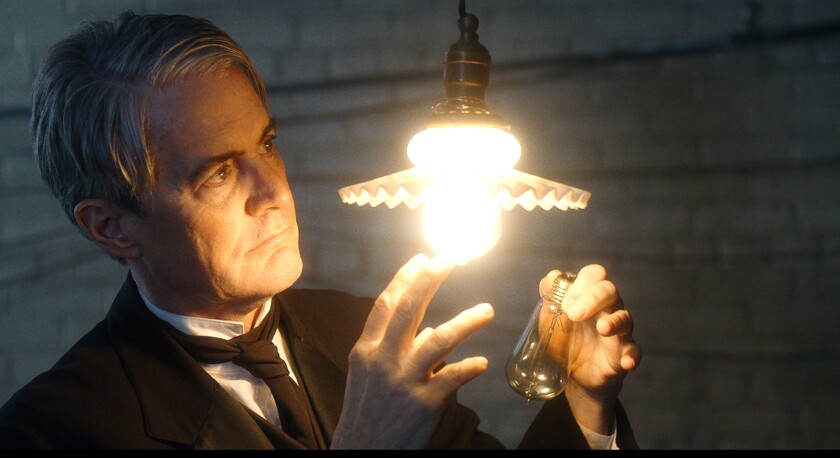

The movies have done their part to exploit his considerable mystique without necessarily drawing him in from the sidelines: David Bowie played him as the drollest of enigmas in “The Prestige” (2006), and Nicholas Hoult gave us a peek at Tesla the wily young upstart in the more recent “The Current War.” You could say that history itself consigned Tesla to a subordinate role, that of the tragically thwarted genius — remembered as much for his lopsided rivalry with Thomas Edison and his ill-fated dealings with various titans of industry as for his groundbreaking advances in the study of electrical power and wireless communications.

In their quietly entrancing new drama, “Tesla,” writer-director Michael Almereyda and his star, Ethan Hawke, have conspired to give this Serbian-born, American-made visionary his cinematic due. Their aim, superficially stated, is to illuminate how a turn-of-the-century iconoclast managed to anticipate and revolutionize a future that few of his contemporaries saw coming. But Almereyda, never one to embalm unconventional minds in conventional storytelling, has no interest in a mere recitation of his subject’s accomplishments. As in “Experimenter,” his aptly titled, thrillingly unorthodox portrait of the social psychologist Stanley Milgram, he infuses classical narrative with an invigorating formal playfulness.

If “Tesla” emerges a remarkably intuitive match of filmmaker, actor and subject, it is one that took its time coming together. Almereyda wrote the script decades ago (Polish filmmaker Jerzy Skolimowski was eyeing it in the early ’80s), though it wasn’t until recently that the stars aligned and the financing was acquired. There is nothing new about the challenges of bankrolling an intelligent drama for discerning adults, or about the oversights of a film industry where potentially great projects can languish for years. But they are especially worth noting in the case of “Tesla,” which is, in more than one sense, a movie about the uneven distribution of power. It’s the story of a stubborn, uncompromising genius in conflict with a series of dubious benefactors, many of whom want to funnel his gifts into more conventional and lucrative forms.

Almereyda doesn’t belabor the metaphor, and he probably would be the last person to describe himself as any kind of visionary. But it is hard to shake the sense that he and Hawke, who starred in his offbeat Shakespeare adaptations “Hamlet” and “Cymbeline,” have forged a kinship with their subject that goes beyond mere empathy. It is also hard not to view “Tesla” as the latest of Almereyda’s movies — including “Experimenter” and his melancholy futuristic drama “Marjorie Prime” — to explore the intrinsic connections between science and filmmaking, to treat the cinematic medium as a rich amalgam of the rational and the poetic.

It begins with Hawke’s Tesla stumbling around a courtyard on roller skates, then a fairly recent invention — a funny, gently disorienting image of a wildly adventurous mind, forever chasing after new concepts and experiences while often struggling to master its environs. He is accompanied by his friend Anne Morgan (Eve Hewson), a superior skater and the movie’s shrewdly counterintuitive choice of narrator. Providing a rare woman’s voice in a story dominated by the whims and aspirations of men, she adroitly navigates this story from one funny-sad vignette to the next while providing her own crucial perspective on Tesla, one that is by turns appreciative of his genius and critical of his shortcomings.

On occasion, Anne will neatly demolish the fourth wall by whipping out a MacBook and running a Google Image search on some of the movie’s real-life figures — including her wealthy father, banker J.P. Morgan (Donnie Keshawarz) — a nifty fact-checking gag that also ties Tesla’s moment to our technologically advanced present. Sometimes Anne informs us that something we’ve just witnessed didn’t actually happen, just in case you were confused by that scene of Tesla and Edison (Kyle MacLachlan) attacking each other with ice cream cones — a deft, ego-deflating visualization of the rivalry that develops after Tesla asks the veteran inventor to finance his new project.

Since that project is a motor that makes use of alternate current, a more elegant and efficient means of harnessing power than Edison’s direct-current methods, no such support is forthcoming. But if the movie’s Edison is arrogant, thin-skinned and easily threatened, MacLachlan’s witty, sympathetic performance resists the yoke of easy villainy. (It’s an inspired reunion too: MacLachlan played Claudius to Hawke’s Hamlet.) A similar emotional generosity informs Jim Gaffigan’s big-hearted turn as engineer and entrepreneur George Westinghouse, who supports Tesla and makes his AC innovations a force to be reckoned with — at least until the company faces bankruptcy and the two are forced to part ways.

Much of this narrative ground was covered in the 1980 Polish film “The Secret of Nikola Tesla,” a creakily effective dramatization best remembered for Orson Welles’ commanding turn as J.P. Morgan. But the two movies could hardly be more different in style and sensibility. For all its arch devices and anachronisms, including a wonderfully straight-faced, go-for-broke cover of a 1980s pop hit, the effect of Almereyda’s “Tesla” is hypnotic. Carl Sprague’s production design has a quasi-Brechtian spareness; the very air seems charged with a strange and lyrical intensity (deepened by John Paesano’s delicately layered score). Cinematographer Sean Price Williams draws us into a world of dark shadows and richly burnished lighting, cast by candles as well as electric bulbs: We are reminded that this seemingly distant, technologically primitive moment was also a time of extraordinary, world-altering flux.

Tesla is an observer, agent and sometimes victim of that flux: His grand visions are the definition of “ahead of their time,” at times leading him into eyebrow-raising realms of study. And Hawke, without exaggerating or diluting Tesla’s eccentricity, distills the character’s strange, sometimes contradictory essence. He is a man apparently without greed who acquired enormous sums and lost them, a thinker who boldly reimagined the parameters of the possible but was ultimately stymied by those very boundaries. What comes through most in Hawke’s brilliantly internalized performance is Tesla’s intense commitment to his work, as well as his weariness about having to continually explain and defend it to men of deeper pockets and lesser minds. The progress of human civilization can be infuriatingly banal, which doesn’t mean our biopics have to be.