Read The Full Article On: Auto

t’s great to imagine a future of efficient, pleasant transportation that does less damage to our planet. But let’s get real: Revolutions don’t come easy.

I am tackling a couple of questions from readers about my interview with my colleague Neal Boudette about electric cars: When will the cars have longer battery life and more charging options? And will old electric car batteries be a hazard?

Let me first stress: Most environmental experts say that shifting to electric vehicles, particularly combined with generating more energy from renewable sources, can make a big difference in slowing the effects of global warming.

Where’s the Infrastructure?

Readers including Stacy Elwart from Venice, Florida, and Tom Rowe from Stevens Point, Wisconsin, had similar concerns: How can electric cars reach a tipping point if charging isn’t widely accessible and convenient, and when ranges still fall far short of what gasoline cars get per tank?

Brad Plumer, a reporter from The New York Times’ Climate team, explains what is happening to tackle the challenges of charging and battery life:

Many newer electric models, like the Chevrolet Bolt and Tesla Model 3, can go well over 200 miles before needing a recharge. That can be quite practical for most daily trips, but not for longer trips or people who don’t have places to plug in their cars at home.

So some companies, like EVGo, are now building hundreds of fast chargers, which can typically add about 100 miles of range in 20 to 30 minutes. That’s slower than refueling at a gas station, but it can make a road trip more doable. There’s hope that further battery advances could speed up charging times significantly. Automakers are constantly trying to improve the range.

Many local governments and electric utilities are also trying to build networks of public chargers, but it’s a huge undertaking and many cities are way behind. It’s the chicken-or-egg dilemma: Companies are reluctant to invest in chargers until there’s a critical mass of electric vehicles. But some people are wary of buying an electric vehicle without better charging options.

It also can take time for utilities to upgrade their grids to handle more electricity demand.

In the short term, these challenges probably won’t stop electric cars from becoming more popular as battery prices plummet and more governments push away from conventional vehicles. By 2030, electric vehicles are expected to be 20% of new sales in the United States, according to analysts at BloombergNEF.

But, the analysts warned, sales could eventually hit a bottleneck without a major build-out of charging infrastructure. Expect charging to get a lot more attention in the years ahead.

Is There a Car Battery Afterlife?

This one came from Steven Permut in Tucson, Arizona.

The lithium-ion batteries that power smartphones and other gadgets can be an environmental and safety hazard. (Fires at recycling centers are a problem.) Electric cars have really big lithium-ion batteries. It sounds like a potential disaster, if and when large numbers of electric vehicles are eventually put out to pasture.

But Adam Minter, a columnist at Bloomberg Opinion (where we were colleagues) and the author of two books on reuse and recycling, told me that electric vehicle batteries can have a useful second life.

Old stuff, Minter told me, is “a source of an incredible level of innovation — and you’re beginning to see that with electric car batteries.”

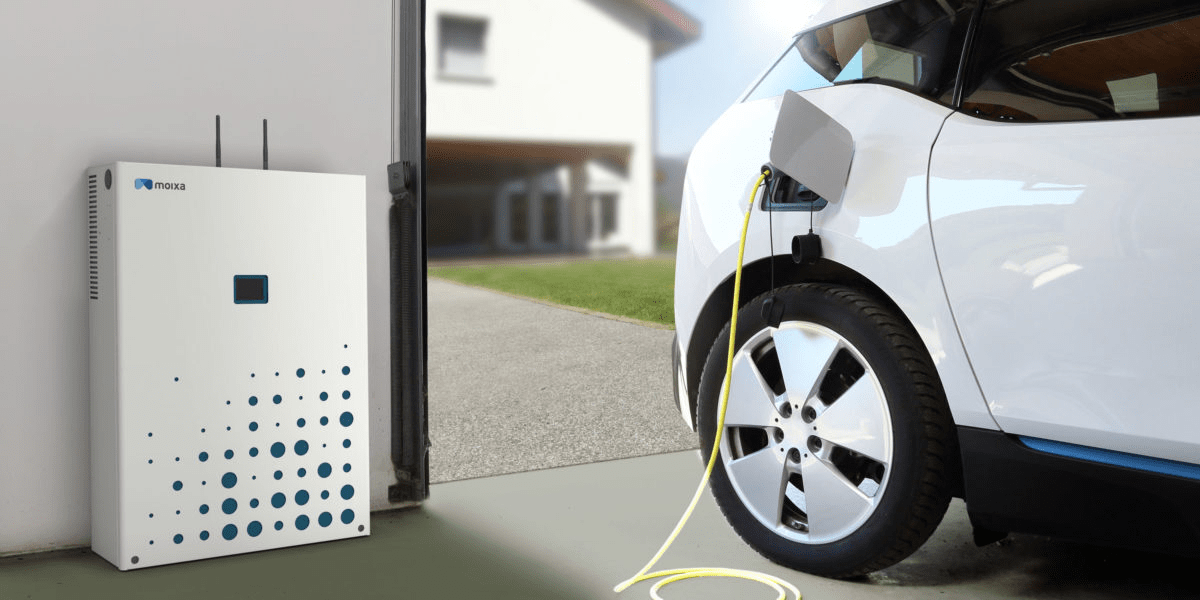

He pointed out eBay listings in which used Tesla car batteries go for hundreds or thousands of dollars. Vehicle batteries with some life left are refurbished to convert conventional cars to electric in some countries or are turned into generators and energy storage, Minter said. And in China, the world’s largest car market, there have been major investments in recycling infrastructure for vehicle batteries. (Although Greenpeace recently said that China wasn’t doing nearly enough.)

Minter still worries about potential environmental harm from manufacturing electric vehicles and their batteries. But, he added, “I’m confident there are good uses” for spent batteries.

Promising Auto Newcomers

Neal also told me about a few younger companies pursuing what he thinks are promising approaches to vehicles of the future — though they’re far from guaranteed to succeed. Here is Neal’s take on three of them:

Rivian is a really interesting company to watch. It’s planning to manufacture its own software-powered electric cars like Tesla — it bought an auto plant in Illinois that had closed. But Rivian is more pragmatic and will follow a lot of established car manufacturing steps that Tesla ignored and then regretted doing so.

Another company, Lucid, thinks it has found a way to squeeze every last bit of energy out of batteries, and it plans to release a car that it says will travel up to 500 miles on a single charge. Lucid’s cars will probably be very expensive— $100,000 or more — but it’s an interesting concept.

There’s another company called Arrival that is working on electric delivery vans and buses with a unique approach: Its vehicles will use giant plastic panels instead of sheet metal. Robots and workers will effectively assemble one vehicle at a time with simplified processes and parts.

Arrival is also talking about manufacturing vehicles in “micro factories” that are close to the eventual vehicle buyers. I don’t know if it will work, but it’s a totally radical way of looking at things. This is not just making another vehicle that doesn’t use gasoline.