Read The Full Article On: Eenews

California must prod 10 million people to buy clean cars and install thousands of charging stations within a decade to start phasing out gas-fueled vehicles in 2035, auto experts said.

An executive order issued last week by Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) would ban the sale of new cars with internal-combustion engines beginning in 15 years. But achieving that level of climate action hangs on a slew of uncertainties, including more renewable energy, increasing EV production, advancements in energy storage technology and the outcome of the presidential election.

That’s just a few of the challenges.

“I don’t want to sugarcoat that it’s going to be easy,” California Energy Commissioner Patricia Monahan said of the massive increase in charging stations. “But I also think that what we’re seeing is a lot of investment by utilities, by private entities, and then supplemented strategically by public dollars.”

Newsom said his edict was necessary to fight climate change as catastrophic wildfires burn across the state (E&E News PM, Sept. 23). So far this year blazes have burned more than 3.9 million acres in the state, killed 29 and destroyed 7,200 structures, California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection data said.

The gas car ban is a first for the United States. Several European nations and provinces in China and Canada have set deadlines for ending new sales of cars powered by fossil fuels (Energywire, Feb. 14).

The governor directed the California Air Resources Board (CARB) to eventually pass sweeping regulations that seek to transform the state’s famous traffic jams into knots of purring electric vehicles.

The rule would have lasting effects on the auto industry, consumers and electricity demand in the nation’s most populous state. Newsom argues it could pour over the borders of California and reverberate through the car industry in other states. California has the world’s fifth-biggest economy.

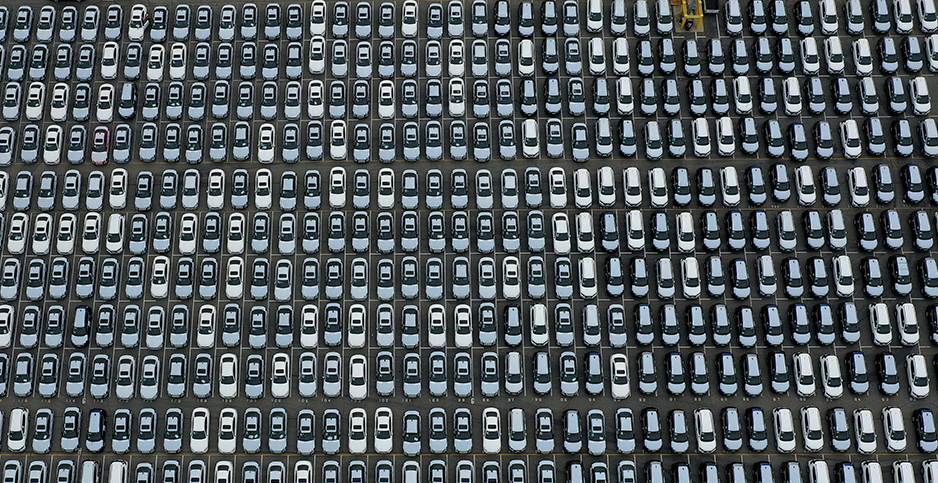

Tailpipe pollution is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the Golden State, accounting for 40%. Roughly 28 million passenger vehicles clog California roads. Right now, ZEVs, or zero-emissions vehicles, constitute less than 2% of the overall fleet.

Clean car popularity has grown, but slowly. ZEVs made up nearly 8% of new car purchases last year, according to the California New Car Dealers Association. Californians buy roughly 2 million new vehicles per year.

“ZEVs are thousands of dollars more expensive than comparable gasoline powered vehicles, if they are available at all,” the auto dealers’ trade group said in a statement.

Residents after 2035 can still own and sell used gas-fueled cars under Newsom’s order. People on average keep their cars a dozen years, said Gil Tal, director of the Plug-in Hybrid & Electric Vehicle Research Center at the University of California, Davis. So California needs to increase ZEV ownership to about 10 million over the next decade to get partway toward the mandate’s goal, he said.

It’s possible to ramp up ZEV purchases swiftly, Tal said. More than 10 years ago, Norway imposed extremely high taxes on car purchases, except for those of electric vehicles. Clean cars now make up 70% of the country’s auto sales, he said.

ZEVs will be cost-competitive with similar gas-fueled models within a decade because of falling battery prices, said Shirley Meng, a professor of energy technologies at the University of California, San Diego.

“The technology’s ready; there’s absolutely no doubt about it,” Meng said, arguing that “Newsom should make the [mandate] timeline 2030, not 2035.”

Clash with Trump

November’s election will affect California’s path.

For the past four years, the state has been in a wrestling match with the Trump administration over clean car rules. Trump’s EPA revoked a Clean Air Act waiver that California used to set mileage and emissions standards that surpassed federal requirements.

The Golden State also used the waiver to run its ZEV program, which forces automakers to produce a growing share of clean cars. The state is fighting the Trump administration’s actions in court.

Trump’s reelection could hobble California’s phase out of gas cars, unless the state wins the ongoing lawsuit over the waiver. Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden likely would support California’s plans if he wins the race.

But the legal fight over the Trump administration revocation of California’s waiver could go all the way to the Supreme Court, where potentially a 6-3 conservative majority could decide the result, if Trump’s nominee, Amy Coney Barrett, is approved.

Different scholars have different views on how much the Golden State needs federal cooperation, said Joshua Bledsoe, counsel in the Environment, Land & Resources Department at Latham & Watkins LLP in Los Angeles.

California could say it’s acting to cut greenhouse gas emissions, or it might argue that it’s attacking conventional air pollution. Or both. The state’s authority to address those problems differ under the Clean Air Act, Bledsoe said.

The executive order mandating ZEV-only new car sales after 2035 comes alongside California’s push to cut emissions in the electricity sector. That’s needed for California to reach its ambitious emissions reduction mandates, and its goal of carbon neutrality by 2045. State law requires that electricity generation come from all clean energy sources by 2045.

More ZEVs will mean more demand for electricity in a state hit by rolling blackouts during a heat wave last month, when power demand surpassed supplies.

EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler noted the rolling blackouts in a letter to Newsom criticizing his order. Wheeler said the supply-and-demand imbalance “begs the question how you expect to run an electric car fleet that will come with significant increases in electricity demand, when you can’t even keep the lights on today” (Climatewire, Sept. 29).

Tal, with UC Davis, said adding plug-in vehicles doesn’t tax the grid the way a heat wave does, with the latter prompting air conditioner usage all over the state. ZEVs can be plugged in at any time, including during the day, when there’s plenty of power from solar panels, he said.

2 years for a rule

It could take two years to get a rule adopted for the ban on gas car sales, said Dave Clegern, a CARB spokesman. The Air Resources Board will incorporate the new target into its existing clean cars program.

The rejiggered rulemaking will likely include interim targets, such as what percentage of car sales ZEVs should make up in 2025 and 2030, said Emily Wimberger, a climate economist at the Rhodium Group and previously chief economist at CARB.

Those types of targets send a signal to drivers, she said, and stimulate private-sector investment.

Asked about it, Clegern with CARB said in an email, “that is usually the process, but we’ll need to be farther along to say what, how or if that will be the case.”

The state likely will need to offer greater incentives to motivate ZEV purchases, and will have to find money to pay for its beefed-up programs, experts said. California now offers rebates of up to $4,500 for clean car purchases. Those rebates are in high demand, with limited funding.

Many said it’s too early to put a dollar figure on the state’s costs for banning gas car sales. But wildfires have costs, too, Wimberger said.

“We do need to take the monetary damages that we’re seeing from climate change very seriously,” she added, “and the benefits of taking action, compared to the costs of taking action.”

The California Energy Commission, meanwhile, will analyze how many refueling stations will be needed for battery-electric plug-ins and fuel-cell electric vehicles. The agency also needs to find the best sites for them, said Monahan, the energy commissioner.

The agency already was looking at the issue following a 2018 law that required the CEC to analyze the number of chargers needed for 5 million ZEVs by 2030.

The majority of EV owners right now charge at home and work, but “you do need public infrastructure,” Monahan said. Private investment is coming in, but “what we need to do is break down where the challenges are, and leverage our public money to fill the gaps,” she said.

Finding and using public EV charging can be difficult, said Wimberger, who tested the availability of public chargers when she bought a plug-in Chevrolet Bolt.

She often found that EV stations were occupied or not working near her home in the Sacramento area. And because vendors have different methods of payment, it was a challenge to have all the methods handy.

“That is part of the discussion, trying to simplify charging,” Wimberger said.

Climate revenues affected

Phasing out gas-fueled cars could affect two major state climate programs: the cap-and-trade market for carbon emissions and the low-carbon fuel standard, said Bledsoe, the private attorney. If emissions from oil refineries drop, they’ll buy fewer carbon allowances. And those revenues currently fund climate programs, including incentives for ZEV purchases.

The low-carbon fuel standard gives credits to those who provide fuels with lower carbon intensity, including most owners of EV charging stations. Credits can be sold, with different rules governing where revenues must go, he said. If emissions drop, it could cool that market.

“So it’s a balancing act for the state as they try to calibrate, frankly, what sort of price signal they’re hoping to see for carbon that meets the objectives, that doesn’t crash the economy,” Bledsoe said.

The Air Resources Board also could respond by making the low-carbon fuel standard more stringent, he said.

There are important unknowns that will unfold over the next 15 years, said Andrew Shaw, a senior managing associate at Dentons law firm. One of those is whether commuting habits permanently change following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Several Silicon Valley technology companies have said they’ll let some staff work remotely permanently. Other companies are allowing employees to work at home part-time. That changes wear and tear on vehicles, and could affect car buying decisions, Shaw said.

For the ban on gas car sales to work economically, California needs to inspire other states to pass their own ZEV mandates, said Tal at UC Davis. Many European countries and China are heading toward all ZEVs, and automakers are producing clean cars for those nations.

But California needs to drive action by others, Tal said.

“In order to succeed, it’s really important that the rest of the world, the rest of the U.S., is on a similar page,” Tal said.